The Education Crisis: A Looming Threat to the Future

@Microsoft Bing

By Shabir Sadiq

Pakistan’s education system, which should be the backbone of its development, stands at a crossroads, gravely affecting the younger generations and propelling the nation toward a bleak future. A combination of poor infrastructure, a lack of relevant curriculum, and societal indifference has resulted in a system that not only fails its students but also hinders Pakistan’s social and economic progress. As these challenges compound, the youth—Pakistan’s potential future leaders—are increasingly disillusioned, pushing the country further into the clutches of fundamentalism and economic stagnation.

The foundation of Pakistan’s public education system is crumbling. Schools across the country are marred by inadequate infrastructure, outdated textbooks, and an irrelevant curriculum that fails to equip students with 21st-century skills such as critical thinking, creativity, and conflict resolution. This gap between education and practical life leaves young Pakistanis unprepared to tackle the modern world, rendering their academic achievements futile. The disillusionment is stark when university graduates find themselves either unemployed or stuck in low-paying jobs while less educated individuals, through corruption and nepotism, accumulate wealth. As one Pakistani parent aptly puts it, “How can we convince our upcoming generation that education is key to success when we are surrounded by poor graduates and rich criminals?”

This frustration is echoed across the nation. Even in relatively well-off families, parents and students alike view education as a stepping stone to emigration rather than a path to success within Pakistan. The government’s inability to address the education sector’s shortcomings—ranging from inadequate public spending to the lack of necessary reforms—has only deepened this crisis.

A key reason for this disillusionment is the stark divide between public and private education in Pakistan. Elite private schools, like Karachi Grammar School and Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), offer education with international curriculum, but these institutions remain out of reach for the vast majority of Pakistanis. Graduates of these institutions secure the best jobs, often with global prospects, while graduates from public universities or underfunded rural schools are left competing for low-paying, often exploitative positions.

The system is rigged to benefit the elite, reinforcing economic and social hierarchies. Parents from lower-middle-class backgrounds struggle to send their children to private schools, fearing that their children will suffer from an inferiority complex in comparison to their wealthier peers. This educational apartheid not only stifles social mobility but also crushes the aspirations of young people, trapping them in cycles of poverty.

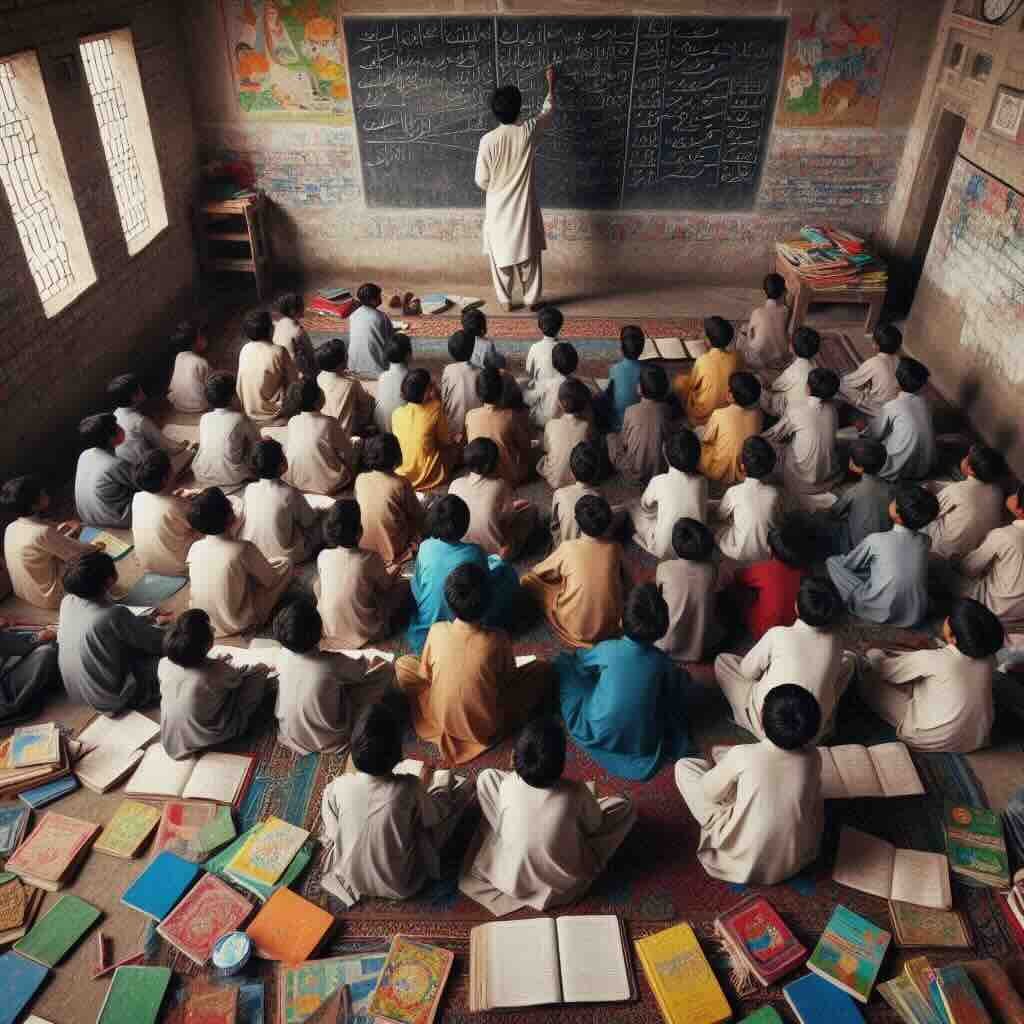

Additionally, the learning environment for public school students is often substandard, with many attending schools with peeling plaster, a lack of basic amenities like electricity, and overcrowded classrooms. These conditions exacerbate the divide between the privileged few and the impoverished many, further entrenching social inequality.

The failure of the education system is more than just an economic or social problem; it has also fueled the rise of extremism and intolerance in the country. An education system that lacks critical thinking and promotes rote memorization over intellectual curiosity leaves students vulnerable to radical ideologies. Young people, frustrated by the lack of opportunities, often turn to fundamentalism as a means of seeking purpose and identity.

Dr. Adil Najam, an academic and global president of the World Wide Fund for Nature, has pointed out that Pakistan’s education crisis reflects broader societal failures. “Literacy is a policy area; education is a policy failure,” he says, explaining that Pakistani society’s lack of demand for quality education allows the system to deteriorate. The result is a population that is increasingly susceptible to extremism because of the limited scope of their education. Without exposure to critical thinking or alternative perspectives, students are left to adopt rigid, simplistic worldviews that can easily be manipulated by extremist narratives.

Pakistan’s education crisis cannot be disentangled from its political system. While Article 25 of the Constitution mandates universal education for all children between the ages of 5 and 16, the reality is that over 25 million children remain out of school. This massive gap reflects not just a policy failure, but a societal one. Policymakers have shown little interest in addressing the systemic issues that plague the education sector, while society itself has not demanded change.

There is a fundamental disconnect between what the government claims and what it delivers. Despite the lip service paid to educational reform, especially at international forums, little has changed on the ground. Efforts to improve public education are continuously stymied by corruption, mismanagement, and a lack of political will. Meanwhile, Pakistan continues to rely on international aid to prop up its failing education system, fostering a dangerous dependency that prevents the country from developing self-reliance and sustainable solutions.

The consequences of this crisis are profound. Pakistan Governments’ failure to provide a robust, equitable education system perpetuates a cycle of poverty and limits the country’s ability to compete on a global scale. Moreover, as more young people grow disillusioned with their prospects, the country risks fostering a generation that is both economically disenfranchised and politically volatile. Without meaningful reform, Pakistan will continue to slide further into extremism and economic stagnation.

Shabir Sadiq (pseudonym) is an Afghan researcher specializing in Pakistan’s education system.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.