Afghan Diaspora Keeps Girls Learning Online Despite Taliban Ban

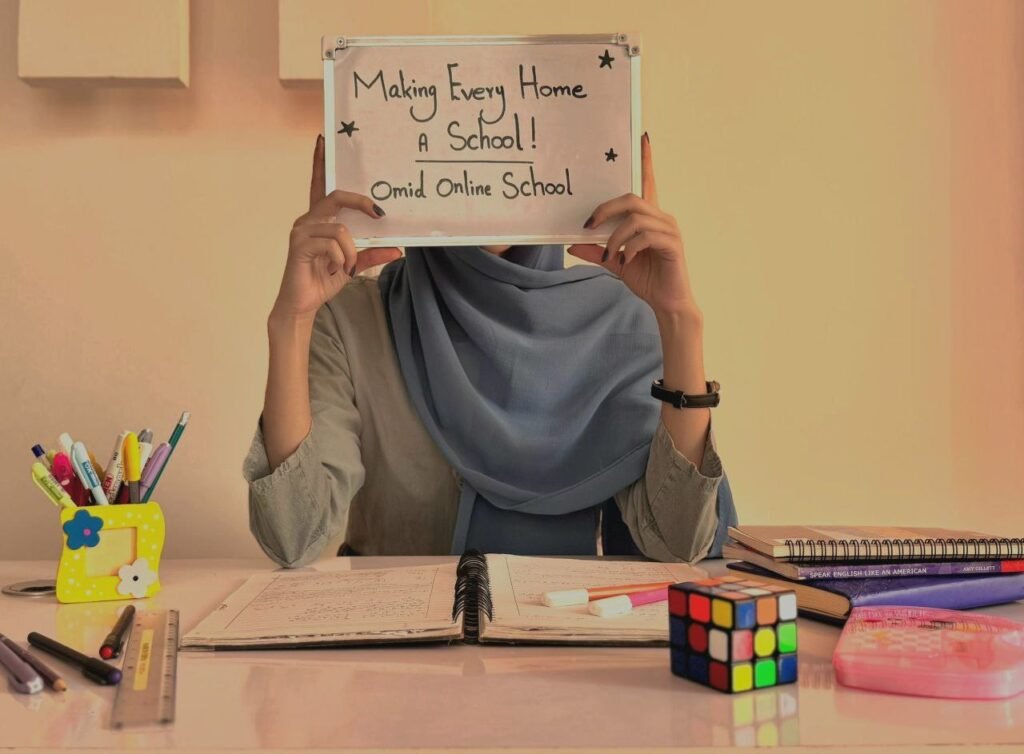

A student from Omid Online School holds a sign featuring the name of the school’s new campaign: Make Every Home a School.

By Ali Ahmad

I first met Zahra Hashimi through her activism for women’s rights and media initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Vienna, where many members of the Afghan diaspora found their voice after the Taliban’s return to power, she was a familiar face at demonstrations demanding justice and education for Afghan women.

When Hashimi launched a virtual school for girls shortly after the Taliban banned education for those beyond sixth grade in August 2021, I was immediately struck by the audacity and compassion behind the idea.

Back then, I interviewed her for an article for the Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation (VIDC), later republished on the Afghan Diaspora Network website. At that time, Omid Online School – “Omid,” meaning hope in Dari, one of Afghanistan’s two official languages, along with Pashto – was an untested digital experiment, run by volunteer teachers and minimal resources.

Four years later, as the Taliban’s rule in Afghanistan reaches its grim fourth anniversary and girls remain locked out of classrooms, Hashimi’s initiative has not only survived but thrived.

In May 2025, she stood proudly at Vienna’s City Hall, accepting the Best Diaspora Engagement Award from the Afghan Cultural Association (AKIS). In her speech, she celebrated the resilience of her students. Later, in September, she launched a new campaign titled “Make Every Home a School.”

It remains to be seen how successful this campaign will be. Hashimi herself is cautious, expressing doubts about whether she will receive meaningful support, either from Afghan diaspora networks working in education or from institutional partners in Austria and beyond.

Curious about what kept her moving forward despite four years of struggle, I asked her again what motivates her to move on with the school for four years.

“We didn’t expect that Omid Online School would last for four years,” Hashimi tells me. “We didn’t start with proper planning. We only wanted to respond to the immediate needs of girls when the Taliban banned education. Now, we can hardly believe we survived this long. It’s more than we imagined.”

Built on Urgency, Sustained by Hope

Omid Online School was never meant to be a permanent institution. It began as a lifeline, a quick, improvised response to the Taliban’s sweeping ban. But in the absence of any formal education system for girls, it evolved into a full-fledged school serving hundreds of students across Afghanistan.

“We didn’t think we had this much capacity to run it for this long,” Hashimi admits. “And we’ve done it without any institutional support.”

Despite its growth, Hashimi says the school remains invisible to international institutions.

“Human rights organizations and educational institutions in Europe shouldn’t see online schools as a pastime,” she insists. “This is a serious lifeline at a critical time for Afghan girls and women. No one – formal or informal – has given us financial, moral, or political support. We’re bringing education to girls’ homes, but our efforts have not been appreciated.”

The school operates entirely online, relying on volunteer teachers and unstable internet connections. Rising data costs and frequent disconnections remain constant threats.

“Internet cuts are a big challenge,” she says. “But we keep going.”

A Teacher’s Dream for Reform

When asked what she would change if she could reform Afghanistan’s education system, Hashimi’s answer is clear.

“If I could change one thing, I would remove the Taliban completely from the Ministry of Education,” she says firmly. “The ministry is not for people with no education. I would make education mandatory for every girl and boy, even if it required separate schools or strict rules. But I would never ban girls from learning. I would make the curriculum more progressive and raise the quality of education.”

Her vision is not political but deeply personal – shaped by her years as a teacher, an exile, and an advocate who refuses to let ignorance define her country’s future.

Students Who Found Light in Darkness

For her students, Omid is more than a school; it is a symbol of survival. Fatema – like many Afghans uses one name, who joined three years ago, says Omid pulled her out of despair.

“I got to know Omid when I was going through very difficult circumstances,” she says. “The school was like a light in the darkness for me. It helped me come out of depression and gave me hope again.”

Fatema says Omid gave her space to explore her true talents.

“In traditional schools, we rarely had the chance to discover ourselves. Here, I grew academically and artistically. Managing the school online library was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life.”

Another student who asked me not to disclose her name for security reasons as she lives under the Taliban and fears them. She is a twelfth-grade student who began with Omid in ninth grade, says the school’s name captures its essence.

“Omid created in me a hope that never fades,” she says. “For four years, it has kept me from giving up. I want to study dentistry and serve others by easing their pain.”

Four years on, Omid Online School is not just a classroom in the cloud, it’s a movement born from the Afghan diaspora’s determination to preserve learning against the odds.

From her apartment in Vienna, Hashimi continues to lead classes, coordinate teachers, and send messages of courage to Afghan girls who log in from across provinces, often in secret.

“We only wanted to give girls a chance to learn,” she says. “Now, Omid has become part of who we are.”

As Afghanistan’s girls remain silenced in classrooms, Omid Online School stands as living proof that education and hope can never truly be banned.

Ali Ahmad is a Vienna-based researcher focusing on migration and diaspora studies.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.