The Interconnected Web of the Afghan Drug Trade: Cartels, Trafficking Routes, and Government Complicity

By *Hamid Pakteen

The clandestine operations of drug smugglers, spanning across the mountains of Balochistan province along Pak-Afghan border, have a long and intricate history that dates back to the colonial era. These smuggling convoys skilfully navigated through British India’s North West Frontier, evading the scrutiny of three empires, as they transported a wide array of contraband such as liquor, opium, automobile parts, sewing machines, and silk. Despite the risk of execution, the native cunning of the smugglers allowed them to outsmart imperial law. Even individuals with close ties to the British Customs Frontier Guards and the Persian king’s Zahedan Road Guards Department were involved in these illicit activities.

Fast forward to the present day, and the modern successors of these networks are inundating the Indian Ocean with a tidal wave of Afghan-made drugs. Recent reports have revealed significant drug seizures in the Gulf of Oman and Indian naval operations, indicating the scale of this issue. European ports, including Felixstowe, Antwerp, and Rotterdam, have witnessed the arrival of narcotics bearing Afghan cartel trademarks, cleverly concealed within legitimate container shipments. The smugglers, reminiscent of their colonial-era predecessors, continue to serve as the economic backbone of impoverished communities in Afghanistan and Pakistan. These smugglers maintain close links with Pakistan Army establishments to operate under the radar with impunity.

Tribal groups in Baloch such as Bizenjos and Kalmatis, who historically dominated the town, now play a pivotal role in the Afghan drug trade. Led by ganglord Seth Gunj Bakhsh and his brothers Seth Murad Jan and Imam Bakhsh Fauji, the fishing fleet of Pasni and Lasbela has become instrumental in storing and transferring Afghan drugs, such as heroin and methamphetamines, through fishing boats to larger ships or small ports across the Indian Ocean rim. Recent arrests have unveiled the direct involvement of fishing-fleet workers from nearby hamlets, highlighting the deep-rooted ties between drug trafficking and the local economy.

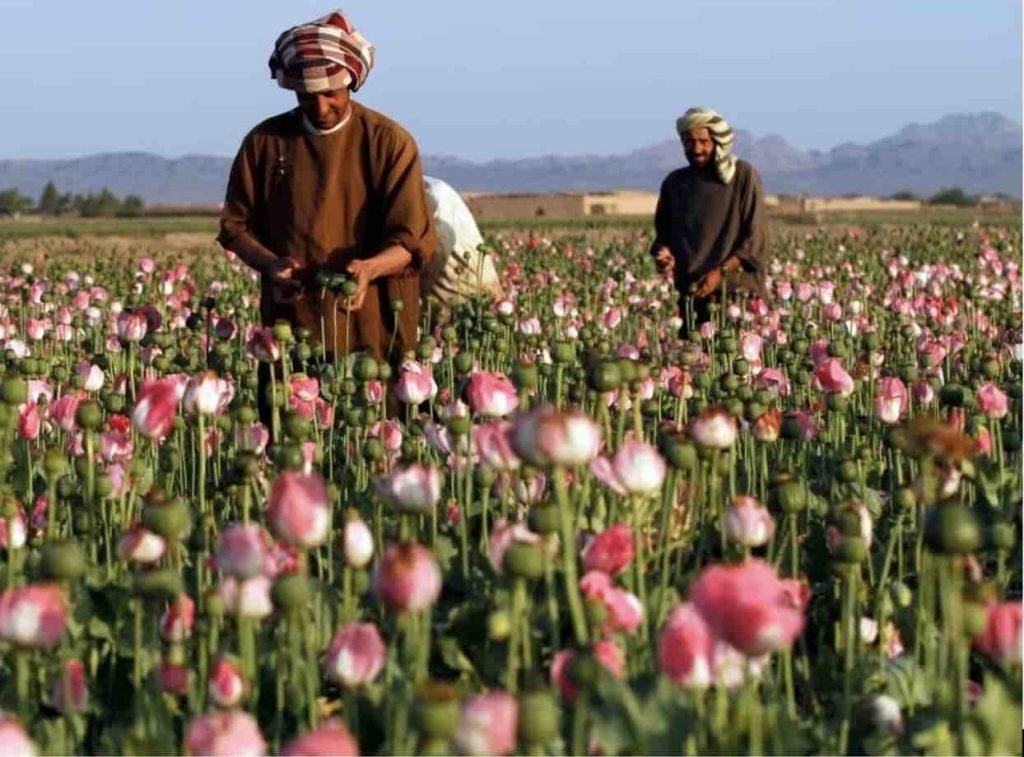

The narcotics trade from Afghanistan involves various interconnected economic activities. Cartels provide farmers with advances to cultivate opium and ephedra, maintaining a symbiotic relationship with the Taliban as their financial support sustains the jihadist proto-state. These cartels also facilitate the procurement of chemicals needed for drug production, relying on sources in Pakistan. Turbat’s Overseas Colony, an enclave of opulence covered in glazed tiles, serves as a hub for top traffickers who operate within an intricate web of criminality. Hostages from various nationalities are held captive until their cartels pay for the delivery of drugs, while terrorist groups provide security services in exchange for payment.

The rise of heroin production can be traced back to the 1979 era when Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate encouraged jihadist groups to generate funds through drug trafficking. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s regime fostered an ecosystem of government protection for heroin dealers, officials profiting from the trade, and significant political influence of heroin syndicates within the government. The subsequent institutionalization of these cartels occurred during the first Taliban emirate, with cartels enforcing their control and resorting to extreme measures such as threatening farmers who refused to cultivate poppies. Trafficking routes extended to Europe, passing through Iran, eastern Turkey, and central Asia to Russia.

Though in its 2nd regime, Taliban have announced a ban on poppy cultivation, use, and trafficking, it is not the same on ground. With no alternate source of income, poppy cultivation is going on full swing. The cash-strapped Taliban government has been unwilling to enforce its ban because the illicit opium trade remains a major source of revenue. Income from opium production, estimated at between $1.8 billion and $2.7 billion, made up 12-14 percent of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product in 2021. It is seen that despite the ban on cultivation, there has been a 34% jump in opium production in Afghanistan.

On the other side of the border in Pakistan, there has been a surge in use of crystal methamphetamine, commonly known as “ice,” particularly in the northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which shares a border with Afghanistan. Health professionals estimate that addiction to crystal meth is increasing rapidly, with around 85 percent of individuals seeking treatment at rehabilitation centers are being ice addicts. Many of whom are young people, including university students. Meth is highly addictive and can be consumed through various methods, offering users a euphoric high that can last for hours.

Crystal meth’s prevalence and affordability make it attractive to young people in Pakistan. It costs around $1.80 per gram, compared to the initial price of $18 when it first appeared in Pakistan in 2018. Crystal meth has surpassed cannabis and heroin as the drug of choice in Pakistan, and many individuals who used to consume other drugs have switched to ice.

The drug trade from Afghanistan to Pakistan remains largely unchecked due to weak investigation procedures and lenient court rulings that allow drug smugglers to evade significant punishment. Afghanistan has become a significant supplier of crystal meth since 2017 when drug traffickers realized that the native ephedra herb could be used to produce ephedrine, a key ingredient in meth production.

The accurate number of meth addicts in Pakistan remains unknown due to the country’s conservative and religious nature, which discourages seeking treatment for addiction. However, past reports estimate that nearly 7 million people, or 6 percent of the population, were addicted to drugs in Pakistan. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had the highest prevalence of drug use, with nearly 11 percent of the population using illicit substances.

Efforts to combat the drug industry through military force have proven largely ineffective, with air raids on Afghan drug processing plants inflicting minimal damage while incurring substantial costs. The implosion of state structures in Afghanistan and Pakistan has further complicated counter-narcotics efforts, as formal policing is limited, and tribal groups complicit in the narcotics trade undertake subcontracted operations. However, countries like Portugal have achieved success by decriminalizing drug use for personal consumption and focusing on demand reduction. The dire consequences of methamphetamines and heroin continue to plague communities, reminding us of the compromises made during the Cold War as the war on drugs was sacrificed for broader geopolitical goals.

* Author chooses a single pseudonym. Pakteen is a researcher based in Afghanistan.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.