Afghans’ Displacement History to Austria

By Ali Ahmad

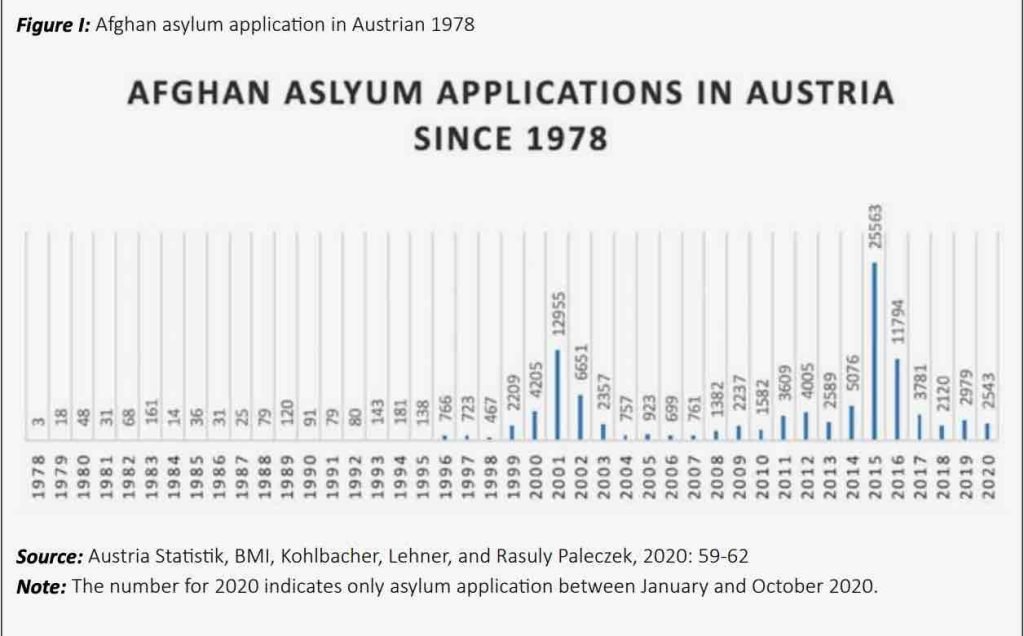

The Afghan population constitutes the tenth largest number of foreign nationals in Austria, with over 44,000 living in the country as of 1 January 2019. Nearly half of that population lives in Vienna.[i] They arrived in Austria as asylum seekers at different phases of the war in Afghanistan, which began when the Soviet Union troops invaded in 1979.[ii] Prior to that, only a few dozen Afghans, mainly students, lived in Vienna. Only three Afghans sought asylum in Austria in 1978, when the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) conducted a coup against the first President ofAfghanistan, Daod Khan.[iii]

The Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan, between 1979 and 1989, formed the first phase of mass out-migration of Afghan people. In the first year of the war, when the Soviet troops marched into Afghanistan, 18 Afghans applied for asylum in Austria.[iv] Political turmoil, mass murder, serious human rights violations and drought, among other reasons, were the driving factors forcing millions of Afghans out of their country.[v] During the ten years of the Soviet invasion, a total of 631 Afghans applied for international protection just in Austria. They were young males from certain elite groups, with a good education and a background of political involvement in Afghanistan. Some left Austria in later years, migrating to the US and Canada.[vi]

Post the Soviet invasion, during the subsequent civil war and brutal Taliban regime that lasted throughout the 1990s until 2001, over 22,000 Afghans applied for asylum in Austria. The demographic of Afghan refugees during the 1990s was more diverse than that of the previous decade. They were no longer only the members of the former communist government and PDPA, but also working women, whose rights and freedom were extremely limited during the civil war and by the Taliban government. The Taliban banned women and girls from work and acquiring an education. Music and other types of entertainment were considered a crime. Violators of the Taliban’s decrees faced lashing, torture, amputation and execution as routine punishments.[vii] Minority ethnic groups, such as the Hazaras, who were oppressed and persecuted during the Taliban rule, also found their way to Europe, and Austria in particular.[viii] In 2001, Austria received a record number of 12,955 asylum applications from Afghans.[ix]

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the US-led coalition forces ousted the Taliban from power for harboring Osama bin Laden and his Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Hope for peace, prosperity and a new Afghanistan began to grow. The figure indicates that in the post-2001 era, the number of Afghan asylum applications in Austria dropped from thousands to its lowest of 699 in 2006. Applications started to increase again as the Taliban took control of vast parts of Afghanistan, having regrouped and rearmed in their sanctuaries in Pakistan, with military and intelligence support from the Pakistani establishment.[x] As the security situation worsened with the increased presence of the Taliban, Afghans again fled the spreading violence, and the number of asylum applications by Afghans in Austria correspondingly increased. In 2008, Afghans lodged over 1,300 asylum applications, and by 2014, more than 5000.

The US-led international forces pulled out their combat troops from Afghanistan and redefined their engagement to “assist, train and advise” the Afghan security forces. The political, economic and military transition in 2014 left behind a large economic and security vacuum. The military and economic transition also affected population movements. In 2015, during the refugee influx in Europe, nearly 180,000 Afghans applied for asylum in the EU Member States,[xi] with Austria, as a one of the Member States, receiving over 25,000 asylum applications.[xii] The Afghans that arrived in Austria since 2015 have a different socio-economic background to those who came during 1980s and 1990s. This time, a large number of Afghans from all ethnic and religious groups, including Afghan Hindus and Sikhs, fled Afghanistan, or left their first country of asylum (for instance, Iran and Pakistan) where they had been born or had lived for most of their lives.[xiii]

Between 2016 and 2019, an additional 20,674 Afghans applied for asylum in Austria. During Covid-19, between 1 January and 31 October 2020, 2,543 Afghans filed new asylum applications in Austria. In the same period the year before, 41% of applicants were granted asylum, 43.2% of applicants were rejected and the remaining 15.8% were in the category of “other”.[xiv] This is because, in response to the influx of arrivals, the focus of Europe’s Member States shifted from providing quick and ‘short-lived’ responses of welcome and open borders to strict policies of ‘migration management’ and border control. At the same time as deporting Afghan refugees to danger, Austria warned its citizens not to travel to Afghanistan. It has designated Afghanistan as an unsafe country. Among the many reasons for the travel ban are Afghanistan’s violent conflict, frequent terror attacks and criminality.[xv]

[i] österreichischer Integrationsfonds (ÖIF), (2020). Migration Und Integration 2019. Available at: https://oeifb2c.wertpraesent.com/migration-und-integration-2464.html[Accessed 31 December 2020], p.30.

[ii] Kohlbacher, Josef, Lehner, Marie, and Rasuly-Paleczek, Gabriele, (2020). Afghan/Innen/En In sterreich: Perspektiven Von Integration, Inklusion Und Zusammenleben. Available at: https://epub.oeaw.ac.at/9783700188155 [Accessed 13 November 2020], p.58; Monsutti 2008, p.60;

Van Hout, Marieke, (2016). Return migration to Afghanistan: Moving back or moving forward?. Palgrave Macmillan, p.42.

[iii] Kohlbacher et al. 2020, p.58.

[iv] Ibid

[v] Jazayery, Leila, (2003). The migration-development nexus: Afghanistan case study. In: Van Hear, Nicholas, and Sorensen, Nina Nyberg

(eds.), The Migration Development Nexus. United Nations, International Organization for Migration, p.215.

[vi] Kohlbacher et al. 2020, p.61.

[vii] Van Hout, Marieke 2016, p.45.

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Kohlbacher et al. 2020, p.61.

[x] Maizland, Lindsay, and Laub, Zachary, (2020). The Taliban in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan[Accessed 26 December 2020].

[xi] Parusel, Bernd, (2018). Afghan Asylum Seekers And The Common European Asylum System. Available at: https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/laenderprofile/277716/afghan-asylum-seekers-and-the-common-european-asylum-system [Accessed 31 December 2020].

[xii] Bundesministerium Inneres (BMI). (2020). Vorl ufige Asylstatistik: October 2020. Available at: https://www.bmi.gv.at/301/Statistiken/files/Jahresstatistiken/Asyl_Jahresstatistik_2015.pdf [Accessed 31 December 2020].

[xiii] Kohlbacher et al. 2020, p.65.

[xiv] „Other“ refers to asylum applications that were withdrawn, suspended or discontinued. This happens mainly when, due to the Dublin Regulations, another country is responsible for processing the asylum application or the asylum seeker can no longer be found in the country (BMI, (2020) https://www.bmi.gv.at/301/Statistiken/files/2020/Asylstatistik_Oktober_2020.pdf p.47).

[xv] Schreiber, Dominik, Reinbenwein, Michaela, Atzenhofer, Wolfgang, Holzer, Elisabeth, Schrenk, Julia, Kada, Kevin, and Zach, Katharina, (2018).“ Österreich: Groß angelegte Abschiebungs – Aktion läuft”. Kurier. Available at: https://kurier.at/chronik/oesterreich/oesterreich-gross-angelegte-abschiebungs-aktion-im-laufen/400016968[Accessed 20 October 2020].