Pakistan: Military Overreach and State Denial Fuel a Violent Phase of Insurgency in Balochistan

Photo: @Balochistan Human Rights Council

By Kadeem Baloch

Balochistan has long been Pakistan’s most neglected region, despite its vast landmass and abundant untapped natural resources, including coal, copper, gold, and natural gas. The Baloch people have revolted against federal authority five times since 1948. What is now unfolding is the sixth rebellion, and it is by far the most sophisticated, lethal, and consequential. Unlike earlier uprisings that could be contained through coercion and co-optation, this one has evolved into a province-wide insurgency capable of temporarily seizing towns, executing coordinated multi-district strikes, and projecting force beyond. The spillover potential into Iran and Afghanistan makes this a regional security crisis. Therefore, it appears that Pakistan’s military establishment is failing to control local insurgency in Balochistan, and in the absence of any political solution, this new phase of violence may further intensify in the coming months.

The scale of violence in 2025 tells a damning story. Balochistan witnessed at least 254 attacks that year, a 26 per cent increase over 2024, resulting in more than 400 deaths (Al Jazeera, 2 February 2026).[1] The BLA alone claimed 521 attacks, asserting over 1,060 security force deaths. In January 2026, the BLA launched “Operation Herof 2.0,” storming military installations, police stations, and a prison across at least ten districts simultaneously. The Pakistan army required three days, deploying helicopters and drones, to retake Nushki from BLA fighters who had seized six administrative buildings. The subsequent counterterrorism “Operation Radd-ul-Fitna-1” concluded at the end of the 3-day siege, underscoring how badly the Pakistani state had lost control in Balochistan.[2]

At the centre of Pakistan’s security response stands Field Marshal Asim Munir, who commands near-absolute authority without meaningful accountability. The military’s approach has been overwhelmingly kinetic: more operations, more raids, more aerial strikes. Balochistan’s Chief Minister, Sarfraz Bugti, boasted in January 2026 that security forces had “sent more than 700 terrorists to hell” over the preceding year, but body counts have never resolved genuine sociopolitical issues. Decades of security operations have only deepened Baloch alienation and produced fresh recruits for the insurgency. In December 2025, religious scholar Maulana Manzoor Ahmed Mengal publicly stated the government had effectively lost control over large parts of Balochistan, and that the Chief Minister could not travel to Khuzdar without a helicopter. Other politicians like Maulana Fazlur Rehman have also warned that in some schools of the province, Pakistan’s national anthem could not be sung, and the flag could not be hoisted due to fear of retribution.

The human cost of this military-first approach is staggering. The Baloch human rights organisation documented 1,355 cases of enforced disappearance and 225 extrajudicial killings in 2025. UN experts have on multiple occasions urged Pakistan to address these violations, expressing alarm at the “unrelenting use of enforced disappearances” and warning that proposed internment centers could lead to “gross human rights violations, including arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances and torture.” In a separate statement, UN experts demanded the release of detained Baloch human rights defenders, including Dr Mahrang Baloch, and called on the government to stop abusing counter-terrorism measures against peaceful activists. Victims of these harsh actions include women, children, students, and the elderly.

It is this cycle of repression that feeds the local insurgency in Balochistan. Every disappearance, every killing, every bombed village creates new grievances and new recruits. The normalisation of drone strikes on civilian areas, weaponisation of anti-terrorism laws against peaceful movements like the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), and persistent information blackouts – mobile internet was shut across all 36 districts for weeks in August 2025, severing 8.5 million subscribers – have convinced many Baloch that peaceful channels for redress are closed. The EU monitoring mission that visited Pakistan in 2025 flagged enforced disappearances and internet shutdowns as areas of “grave concern,” raising questions about Pakistan’s compliance with GSP+ trade preferences.[3]

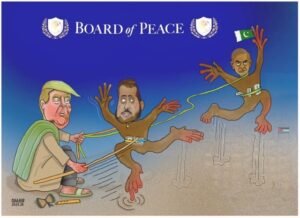

Rather than confronting these root causes, the Pakistan military has doubled down on externalising blame. In May 2025, the Ministry of Interior directed all federal departments to refer to Baloch insurgent groups as “Fitna al-Hindustan” (“The Mischief of India”) – framing a decades-old domestic insurgency as a foreign conspiracy. Interior Minister Mohsin Naqvi, within hours of the January 2026 attacks, declared India was behind them without offering any evidence. The overnight discovery of BLA-Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan collusion, the Chief Minister’s claims about Afghan soil being used as a base, and other external involvement allegations serve a narrative purpose rather than a strategic one. Several international media outlets uncritically amplified Pakistan’s claims of “external involvement.” Without any credible proof, all these allegations are just part of the military’s misinformation campaign designed to deflect from its own failures.

The strategic logic of blaming India and Afghanistan is transparent. Pakistan’s economy is in severe distress, its provinces are politically turbulent, and a full-scale confrontation with either neighbour is unaffordable. But limited provocations or the use of non-state proxies remain on the table, particularly when external actors – China, protecting CPEC investments, and the United States, with its own interests – may look the other way. The BLA’s designation as a terrorist organisation by the US and EU gives Islamabad diplomatic cover. However, none of this addresses the fundamental grievance that Balochistan’s vast resources generate revenue for the federal government while the province remains the country’s poorest, a dynamic that has persisted for seven decades.

Balochistan needs genuine political engagement, economic equity, an end to enforced disappearances, accountability for security forces, and space for peaceful dissent. The Baloch groups have in the past tried to negotiate with Pakistani state authorities, but Islamabad failed to reciprocate with political concessions, and the opportunity has been squandered. Field Marshal Asim Munir commands full authority in Pakistan and his decisions will decide the future of peace and tranquillity in the province. What he lacks is the strategic imagination to see that no military can kill its way out of an insurgency rooted in legitimate grievances. Until Pakistan’s military establishment recognizes this, which is unlikely, the local insurgency will keep growing, and the Baloch will remain trapped in a cycle of state violence and armed resistance that benefits no one, least of all the people of Balochistan.

The author chooses a pseudonym. Kadeem Baloch is a freelance journalist based in Pakistan.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.

[1] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/2/2/how-balochistan-attacks-threaten-pakistans-promises-to-china-trump

[2] https://www.dawn.com/news/1971222

[3] https://gsphub.eu/country-info/Pakistan#:~:text=Economic%20Impact%20*%2090%25%20A%20large%20share,of%20zero%2Dduty%20imports%20from%20Pakistan%20in%202024.