From South Asia to Middle East: Pakistan’s Expanding Destabilization Activities

@Tariq Shahid

By Rahmatullah Achakzai

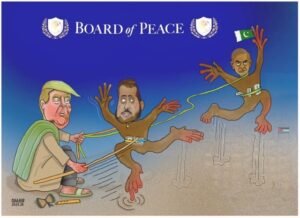

Pakistan has entered Middle Eastern politics in a way that looks less like quiet diplomacy and more like strategic entanglement. The clearest marker is the September 17, 2025, “Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement” between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, which publicly framed “any aggression” against either as aggression against both. However, the text is not public, and that ambiguity is exactly the point; it is a political signal designed to deter adversaries, reassure partners, and advertise Pakistan as the only Muslim-majority nuclear power that can credibly play “extended deterrence” politics in the Gulf region. The destabilizing risk is that such ambiguity will likely invite miscalculation, because regional actors may act more aggressively, believing that Pakistan’s deterrent shadow will constrain responses.

That risk is growing as Turkey reportedly seeks to join this Saudi-Pakistan pact, turning a bilateral arrangement into something closer to a trilateral security framework. Media reports indicate that advanced talks and the anticipated pact’s “any aggression” clause mirror NATO’s collective-defence logic. Whether or not the “Islamic NATO” label survives scrutiny, the strategic direction is real. Pakistan is tying itself more closely to Gulf security debates at a moment when Israel-Iran tensions, Gaza spillovers, Saudi-UAE shadow wars, and shifting US postures have made the region unusually combustible.

The second marker is internal to Pakistan. The unprecedented consolidation of military authority after the passage of the 27th Amendment in November 2025 and the way the security establishment increasingly frames Pakistan’s purpose in overtly ideological terms. This centralization of power is inherently destabilizing, and it matters when the military leadership also leans on religious symbolism for legitimacy and domestic mobilization, because it narrows the space for civilian risk-control and makes “virtue signalling” to Islamist constituencies a tool of statecraft.

This is where Pakistan’s relationship with transnational Islamist movements becomes strategically relevant and extremely dangerous for the region’s stability. Pakistan has long been backing and supporting the anti-India activities of the UN-designated terrorist organizations such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM). Even when Pakistan banned these groups under international pressure, they continue to retain a very active operational space via affiliates and front structures. This matters because when Pakistan simultaneously boosts its security footprint in the Middle East, its open support for Islamist terrorist outfits becomes a regional problem, not just a South Asian one.

In parallel, Pakistan’s mainstream political and religious platforms have increasingly provided support to Hamas representatives for propaganda purposes. In January 2024, Pakistan’s Senate hosted Hamas representative Khaled Qaddoumi and senators publicly welcomed him. In February 2025, Qaddoumi participated in an event in Pakistan Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK) and met Pakistani religious, political, and known terrorist figures. This is proof that the Pakistani state is hosting Hamas to motivate local and international terror outfits to target Western countries, Israel, and India.

Hamas is widely designated a terrorist organization by the United States and the European Union, among others, and its fundraising and support networks have been a live enforcement issue in Western jurisdictions. When Hamas figures are treated as honored guests in Pakistan’s political spaces, it creates two downstream risks: first, Pakistan’s domestic Islamist ecosystem becomes a magnet for transnational mobilization narratives; second, Pakistan further vindicates the global narrative that it is a terror-sponsoring nation.

There have been concerns regarding support to Pakistan-based terror groups from Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood. The sheer presence of representatives from these banned Islamist outfits in Pakistan suggests a systematic and operational support for LeT and JeM. Some media reports claim of Hamas-linked figures appearing alongside individuals presented as LeT-linked at events in Pakistan, mostly related to the Kashmir issue. Those reports may indicate contact, sympathy, or opportunistic co-branding by conflating Gaza and Kashmir to garner international attention and enhance funding activities for Pakistan-based terror proxy networks.

Still, the broader pattern is destabilizing even without a courtroom-grade evidentiary chain. Pakistan’s Islamist parties have publicly demanded steps like opening a Hamas office in the country, which, even if not realized, signals political appetite to deepen ties. Separately, OSINT reporting has highlighted Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated participation in large Jamaat-e-Islami gatherings in Pakistan, suggesting Pakistan’s Islamist space is increasingly plugged into wider transnational Islamist networks. These are not neutral linkages. In the Middle East, the Muslim Brotherhood remains a polarizing actor, supported or tolerated in some places and treated as a direct threat in others. Turkey is reportedly a safe haven for the Muslim Brotherhood activities.

The United States has recently designated Lebanese, Jordanian, and Egyptian branches of the Muslim Brotherhood as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO). Many policymakers are demanding that the Trump administration ban the Turkish branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is the most proactive and highly dangerous for regional stability. When Pakistan appears to provide a hospitable arena for such networks, it imports Middle Eastern ideological rivalries into its own policy, and exports its own radical Islamist politics outward.

The final destabilizing vector is strategic overreach. Pakistan’s leadership is signalling that it can be a “security provider” in the Islamic world at the exact time its own domestic security is strained and its neighborhood is volatile. The mutual-defence pact with Saudi Arabia, possible Turkish accession, and Pakistan’s desire for relevance in Gaza diplomacy can easily become a trap. If Pakistan is pulled into the Gulf’s escalation dynamics, its military establishment may respond with the same toolkit it has historically used to exert asymmetric leverage in South Asia, thereby widening the arena of proxy politics rather than narrowing it.

The argument, then, is not that Pakistan is single-handedly driving Middle Eastern conflict. Still, Pakistan has formally deepened collective-defence ties with Saudi Arabia, and Turkey is seeking to expand the defence agreement. Additionally, Pakistan’s military establishment is providing more space to radical Islamist groups like Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood to support local terror outfits like JeM, LeT, etc, and garner support from Islamic nations on Gaza and Kashmir. However, that mix increases the odds of miscalculation, ideological spillover, and proxy entanglement across two already volatile theaters: South Asia and the Middle East. To prevent a new phase of proxy activities and armed conflicts in these regions, the international community should treat Pakistan’s Middle East turn as an urgent risk-management problem.

Rahmatullah Achakzai is a journalist based in Balochistan, covering human rights, regional politics, and cross-border issues.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.