Loyalty and Loss: Witness to the Final Days of President Daoud Khan

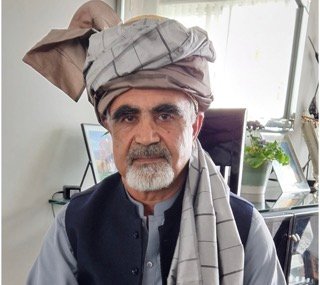

Habib Rahman Habibi, a former military officer and once-trusted aide to Hafizullah Amin - former president of Afghanistan.

By Wakeel Attock

Nearly half a century after the violent collapse of Afghanistan’s first republic, a rare firsthand account has emerged — shedding intimate light on the shifting allegiances, ideological fractures, and harrowing final hours of President Mohammad Daoud Khan.

In an exclusive account, tinged with sorrow and clarity, Habib Rahman Habibi, a former military officer and once-trusted aide to Hafizullah Amin — speaks for the first time about the revolution that reshaped a nation, and the man who tried, and ultimately failed, to lead it.

“We defended Daoud Khan’s republic from day one,” Habibi recalls his memory. “In 1352 (1973), when Daoud Khan overthrew the monarchy, I was serving at Qala-e-Jangi. We, the military officers, were devoted to the cause of the republic. Every afternoon, we gathered under the Pushtunistan flag in Kabul and discussed the future of the new regime.”

Those early days, filled with fervor and promise, quickly gave way to suspicion and betrayal. The People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), initially an ally, began to bristle under Daoud Khan’s increasingly autocratic grip.

Habibi, then an active go-between, recounts tense but hopeful meetings with PDPA leaders Nur Mohammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin.

“Amin told me: ‘We support the republic. We’re ready to collaborate with the state as a united front. Amin even asked me to pass this message to other party members serving in the army. We were to protect the republic in Daoud Khan’s absence. It was a mission of loyalty.”

However, the ideological honeymoon didn’t last. As Islamist factions began plotting against the republic and regional actors mobilized under ethnic and sectarian banners, the PDPA grew suspicious of Daoud Khan’s intentions.

“We saw both religious extremists and nationalist conspirators trying to destabilize the government. We, the party, took it upon ourselves to expose them,” Habibi says. “But when Daoud started consolidating power and cracked down on political pluralism, tensions boiled over.”

According to Habibi, Daoud’s pivot toward authoritarianism — including outlawing parties and rewriting the penal code with harsh provisions — betrayed the inclusive spirit of the republic.

“He silenced everyone. Even then, we didn’t move against him. But when he attacked the party, when he ordered arrests without regard for power dynamics, the party reacted.” Habibi recalls.

A Palace, a Gun, and an Ending

What followed is a chapter of Afghan history often obscured by time and trauma. The April 1978 coup that brought the PDPA to power ended not only Daoud Khan’s presidency, but his life — and the lives of nearly his entire family.

Yet Habibi offers an account darker than most. Citing the late Gulalai — the wife of Daoud Khan’s eldest son — Habibi recounts that Daoud himself may have ordered the killing of his own family, instructing his son to execute them to prevent capture or humiliation.

“It’s a horrific thought, but one that was shared in interviews by close relatives. Daoud reportedly called his family into the Gulkhana Palace and gave his third son, Wais, the order to carry out the executions.” Habibi says, his voice faltering.

The claim, if true, adds a wrenching twist to an already tragic legacy. A recorded interview with Daoud Malekyar, a family relative, is said to contain corroborating details — though the footage remains unreleased.

During the chaos, Habibi says, Daoud was given an opportunity to surrender.

“He was given a message through Commander Imamuddin at Bala Hissar. He was asked to lay down arms. But instead of surrendering, he fired the first shot — and that sealed his fate.” he said.

Even as he recounts the final moments, Habibi does not speak with anger — only grief.

“He had flaws, yes. But he was a patriot. He loved this country. He didn’t deserve that death.”

Echoes of a Shattered Dream

In the decades since Daoud Khan’s death, Afghanistan has seen republics rise and fall, ideologies clash, and generations grow up under the shadow of war. Yet for Habibi, the dream they once defended still flickers — dimmed, but not forgotten.

But for Habibi, the story is far more personal: “We defended Daoud’s republic — not because we were blind followers, but because we believed in a future built on justice and progress,” he says. “When that dream collapsed, so too did a part of Afghanistan’s soul.”

Afghan poet Wakeel Attock previously served as the director of culture for the eastern provinces of Laghman and Nooristan.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.