From Shiraz Back to Kunduz: The Endless Cycle of Afghan Displacement

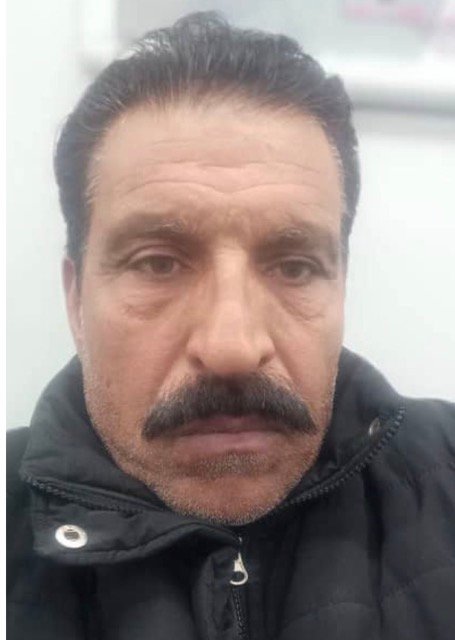

Askar Khan, recently returned from Shiraz, Iran to Kunduz, shared his ongoing experiences of displacement with ADN. Photo: Askar Khan for ADN

By SS Ahmad

Kunduz: When 54-year-old Askar Khan talks about his life, it is not one of settled years but of constant movement, escape, and return. “My biggest hope is to find steady work so we can stay in Afghanistan without leaving again,” he says, sitting in his modest home in Kunduz just weeks after being deported from Iran with most of his family.

His words carry the exhaustion of decades spent in exile, first in Pakistan, then in Iran, then back to Afghanistan, and once more to Iran, only to be forced out again.

For Khan, displacement has been less a chapter in life than the whole story itself. His journey reflects the experience of millions of Afghans whose lives remain defined by borders, deportations, and the endless search for stability.

A Life Shaped by Flight

Khan was born and raised in Khan Abad district of Kunduz. His formal schooling ended abruptly in the third grade, when war forced him into farm labor. By the time he married, violence in his village of Qurghan Tepa — a community divided among Tajiks, Pashtuns, and Uzbeks — pushed him to flee for the first time.

His first stop was Pakistan. He lived in Peshawar and later Karachi, surviving as a day laborer for five years. “Life was very hard,” he recalls.

“We could not even treat my daughter’s heart condition.” Desperate for better conditions, he moved his family onward to Iran, where they eventually settled in Shiraz.

For nearly two decades, Shiraz became both refuge and prison. Khan worked on cow farms while his children tried, often unsuccessfully, to continue their schooling. Refugees were required to carry headcount registration cards, renewed annually, but even basic necessities were rationed. “There were quotas for bread,” Khan says. “Men and women stood in separate lines. Refugees could not buy freely like Iranians.”

The constant surveillance and restrictions weighed heavily. Police harassment was routine. “I was arrested twice. Once, just for carrying a small knife in my pocket. They accused me of robbery and extorted money. They insulted us, calling us ‘dirty Afghans.’”

Homecoming Without Hope

In 2014, news from home seemed hopeful. With Hamid Karzai stepping down and a new Afghan government under former President Ashraf Ghani in place, Khan thought it was time to return. He sold what little he had saved and brought his family back to northern Kunduz province. But the optimism evaporated quickly.

By 2015, Kunduz had fallen to the Taliban. The family lost their rented home and farmland. “We lost everything again,” Khan says. Faced with renewed instability, they went back to Iran — only to encounter harsher restrictions.

His children managed some education, but financial struggles and the COVID-19 pandemic ended their schooling. One of his sons attempted to migrate to Europe in 2016, a path many Afghans dream of. Twice he was caught at the Iran-Turkey border.

“The second time in 2021, guards tortured him and broke his leg,” Khan recounts. “He now has a metal plate and still hopes to return to Iran for treatment.”

By then, deportations had become routine in Iran. Refugees were ordered to obtain deportation letters within 62 days or face arrest. Families were expelled together under the name of the household head.

“Those who delayed were fined and deported,” Khan says. His family, six members, were sent back through Nimroz to Kabul and then Kunduz.

Struggling for Stability

Deportation brought little support. Each deportee received a SIM card, biscuits, and 2,000 Afghanis (USD 30), barely enough for survival. “The landlords in Iran kept our money,” Khan adds bitterly. “We returned with nothing.”

Now in Kunduz, the family faces unemployment and uncertainty. His married daughter and younger son remain in Iran, living in hiding to avoid arrest. Meanwhile, the Taliban government offers little opportunity.

“Only madrassa graduates or those with Taliban connections get jobs,” he says. Former government workers are dismissed, and ordinary Afghans face mounting restrictions.

While large-scale fighting has subsided, the sense of fear remains. “There is some security, but no certainty,” Khan says. “People believe the Taliban will fall, but no one knows when.”

What he wants most is simple: to stay put. “I want to stay here in Afghanistan,” he says quietly. “I don’t want my children to live the same life of displacement.”

But winter looms, and with no savings, no land, and no job, survival is far from guaranteed. “Our fears now are unemployment, the coming winter, and future instability,” he admits.

Khan’s story captures the cruel cycle faced by Afghan refugees. In Iran, he and millions like him lived lives constrained by discrimination and police harassment, tolerated but never accepted. In Afghanistan, they return only to find instability, unemployment, and political uncertainty.

Three years ago, Khan even registered with UNHCR for resettlement to a third country – possibly to a Western nation. Deportation has now shattered that hope.

“During the Iran-Israel war, Afghans were harassed, arrested, and abused in every province — we lived through hell,” he says.

Still, Khan holds onto a fragile dream. After decades of crossing borders, he wants stability in his homeland. Whether Afghanistan will allow him and his family that future remains uncertain.

For now, he waits in Kunduz, a man who has spent a lifetime in motion, hoping his children’s lives might finally stand still.

SS Ahmad is a freelance researcher and journalist based in, Kabul Afghanistan.

Note: The contents of the article are of sole responsibility of the author. Afghan Diaspora Network will not be responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in the articles.